Efficiently converting SQL results to JSON

March 22, 2021

The technology behind the eKee consents permits to share a subset of data with an infinit granularity and let the request dictate the final structure. In short, provide a zero config query language.

What this means is that eKee is constantly transpiling a JSON request into a SQL one and then converting back the SQL result to a JSON representation. Issue being that this operation is done in realtime, making it performance critical.

For a while, we had a naive implementation working just fine. But with the users having more and more data saved, we detected that when the result started to get big (~50MB), the server could take up to 30s to respond.

In this article I'll explain how a new algorithm, building the resulting tree along the stream, permitted to reduce this response time from 30s to 200ms at worst.

The issue

The goal is to build a JSON object from the results of a SQL request. In our syntax, a JSON object represents an entry in a table and all its fields are the columns of the table plus subobjects if the table have references to other tables.

There is two major issues when transforming SQL results to JSON:

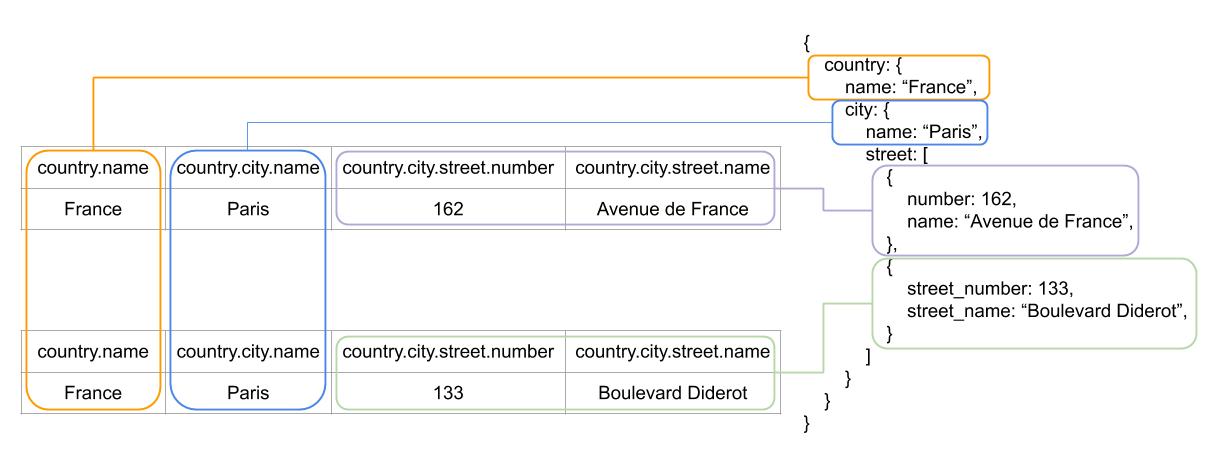

- Objects unicity: The result from a SQL request can be seen as a 2D representation. There is no depth. Therefore, we need to remap all the columns in the resulting row to their corresponding object and then be able to understand the relation between each objects before adding the depth dimension (In Fig.1 we would have three kind of objects: country, city, street);

- Merging identical entries: As for country.city and country.city.street (Fig.1), when multiple elements are present for a similar relation between two tables A and B (i.e. one-to-many), a row is returned for each element from B. Issue being that each of those rows will have similar columns for the related entry A. Even though the resulting object must have only one occurrence of A and an array of B.

The naive approach: building and merging trees

A naive approach to the problem would be to handle each issue one after the other. First you build a tree per row and then you merge all those trees together one after the other.

Since each tree have the same structure, the main advantage of this solution is its simplicity. The algorithm takes each tree one after the other and merge it into the result from the previous merge. When comparing, if the nodes are exactly the sames, you keep the current occurrence (city nodes in Fig.1). But if some of their fields missmatch, you create a branching at the level of the missmatching nodes: an array (street nodes in Fig.1).

But this solution is memory expensive. You build tons of intermediate objects which are just going to be released during the merge. In a programming language with a garbage collector such as Go, this impacts the performance a lot. You are allocating and releasing quantity of objects, forcing the garbage collector to do frequent and long stops.

Moreover, the number of comparaison to do keeps increasing every time you add a new branching into the resulting tree. Meaning that this solution starts showing its limits when the resulting JSON object has multiple arrays.

A more linear approach

The previous algorithm was spending most of its time into the walkthrough and the comparaison of the objects built from the resulting SQL rows. Therefore, the goal of the new approach is to avoid walking through the resulting JSON object and find an efficient way to compare objects.

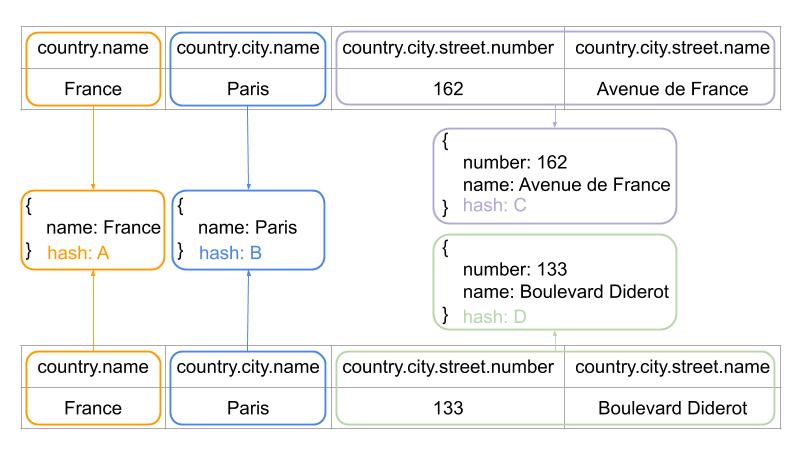

The new solution consists of building all the objects first before linking them to their parent. No more walking through a tree. But in order to be able to compare the objects without a walkthrough we need to be able to hash them. This solution is only applicable if the objects to compare have the same structure. That's a piece of luck, in a SQL response each resulting row has the same columns in the same order.

The whole process is carried out in three passes: First, we build the objects and their hash. Then we walk through the hashes to delete the duplicates and register the different relations between objects. Finally we link the objects between them using the relations found in the latter pass.

Building the objects and their hash

type Route = string

type RowElement = {

object: Object

hash: Hash

parentRoute: Route

}

objects := map[Route]RowElement

// Format SQL rows into JSON object

for col, value := range SQLrows {

path := unalias(col)

// path = "country.city.street.name"

// Route: "country.city.street"

// TableName: "street"

// Column: "name"

// ParentRoute: "country.city"

// ParentName: "city"

route, key := strings.splitLast(path,".")

// build hash + add RowElement/field if needed

objects.AddKeyToObject(route, key, val)

}

To make the construction of the JSON feasible, all the columns in the SQL query have been previously replaced by a path to the place where the values should be put in the final JSON. It is thus possible to track the position of a field but also that of the object that owns the field, the parent object, etc. However, the number of columns in each object is unknown before the end of the processing. The identifiers of the objects generated for a row can only be used after the processing of all the columns of the row.

The identifier of an object is enriched as columns are added to it. Field names are omitted during the generation of the identifier to limit the size of the data to process. The coupling of the path leading to the object to its values ensures that two objects from different tables cannot be confused. Even if they are made up of the same values.

Since some tables may not have selected columns, calls to AddKeyToObject will ensure that all objects present in the field's route are created. In our example (country.city.street.name), adding the name field will create empty objects for the country.city and country routes in addition to adding a name field to the country.city.street object

Deleting duplicates and finding the relations between objects

type AllElements = map[TableName]HashList

// Use generated hash to reduce the number of JSON objects

// and link objects

for objRoute, obj := range objects {

// Append to known json objects

// permitting to use the same memory

// for all equal objects (same structure & values)

jsonObj, has := objectsMap.get(objRoute, obj.hash)

if !has {

objectsMap.put(objRoute, obj.hash, obj.object)

}

parent := objects[obj.parentRoute]

// Inserting in the hash list, to remove duplicat objects

// (Behaves like a hashset)

// One hashset per table

objHashList := allElements[objRoute]

objHashList.Insert(Table{

parentHash: parent.hash,

parentTable: obj.parentRoute,

hash: obj.hash,

})

}

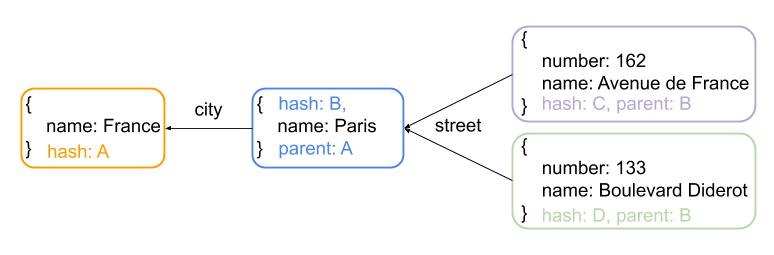

An important point of this second step is how the hash table is handled. The order of arrival of the elements must be preserved so that, if ORDER BY is used in the SQL query, the order of the elements in the JSON are well sorted. The objects are grouped according to their parentHash and parentTable and then the arrival order is used. The hash is therefore only used to check the equality between two objects.

Building the final JSON representation

type ObjectsMap = map[Route][Hash]Object

// Prepare the destination object for all the Table which

// do not have a parent

res = {}

ObjectsMap[""][""] = res

// Link final objects together

for objectRoute, hashList := range allElements {

hashMap := ObjectsMap[objectRoute]

for _, el := range hashList {

currentObj := hashMap[el.hash]

parent := ObjectsMap[el.parentTable][el.parentHash]

_, tableName := strings.splitLast(path,".")

// Insert Or Append field if already present

parent[tableName] = currentObj

}

}

// return the only object whose route is ""

for _, res := range ObjectMap[""] {

return []Object{res}

}

// return an empty array representing nothing found

return []Object{}ObjectsMap contains all the generated JSON objects and AllElements the links between these objects. During this last step, there are no more complex calculations or algorithms to apply. Inserting the new elements is not super interessting but nonetheless verbose, which is why the insertion code is omitted. Arrays should be created if an element is already present in the tableName field.

In the example above, two different objects will be connected to the same parent object using the street field. An array will be used to keep both objects.

Results

Switching from the first to the second solution allowed us to significantly reduce the execution time of some of our queries. Previously, processing about 50MB of SQL results could take over 30 seconds. Now, this same processing consistently takes less than 200 milliseconds.

However, the implementation presented today remains naive and largely optimizable. Among the most impactful optimizations we can think of:

- Use a more compact representation for the hashes,

- Replace Map by arrays in order to suppress the generation of Go hashes and take advantage of contiguous memory storage,

- Use memory pools when creating objects,

- Implement vectorization during comparisons

But as a wise man once said: premature optimization is the root of all evil! Therefore they will only be implemented when the need arises ;)